Author’s note: Another week. Another pre-professional article. I’m riding this wave of inspiration for as many weeks as I can, before returning to our scheduled programming!

When I was a consultant at McKinsey, I had no idea how a company actually worked.

Seems like a crazy statement, but hear me out.

As a consultant, I spent a lot of time hyper-focused on one specific part of a company. Either I was embedded deep into a function, or I was pie-in-the-sky opining about the future of an industry in 3–5 years.

So at the time, I knew a ton about how an HR department organizes its compensation bands. And I knew a ton about the macrotrends of the debit card market.

But I didn’t know anything about how a company actually operated. I didn’t know what a sales pipeline was, I didn’t know how digital marketing was optimized, and I definitely had no idea what engineers did.

Worst of all, I didn’t know how it all fit together — how all the teams combine to form what we know today as a company.

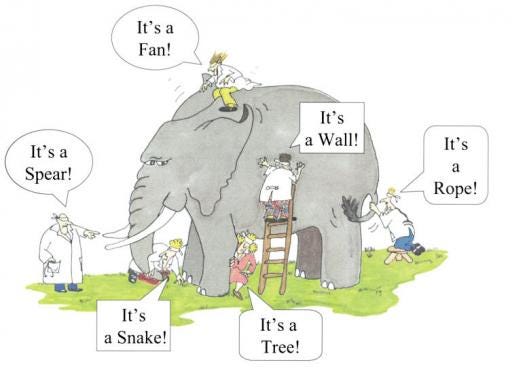

It was like the fable of the blind men touching an elephant. I had a really good sense of what the proverbial elephant’s trunk felt like, and I mistakenly thought that I knew what an elephant was. But I never truly saw the big picture until I left.

So imagine my confusion when I began recruiting for tech, and I saw roles called Product Manager, Business Operations, Operations Manager, Product Operations, Strategy, Strategic Partnerships, and Product Marketing — the list goes on.

Going through job descriptions seemed like staring a nonsensical word cloud.

Can you guess what I did when faced with all that confusion and anxiety?

If you guessed that I did the sensible thing, like reach out to a former colleague for advice or go online to research role titles, you guessed wrong.

I winged it.

Chief of Staff, Business Operations, Strategy. It didn’t matter what the role was. As long as the JD had “2+ years of management consulting experience”, I applied.

Luckily, I landed in a pretty good spot working at Ripple.

But it wasn’t until after I had been in tech for 6 months that I finally understand how a company actually worked, what each team did, and how each role contributes to the company’s overall mission.

Hopefully now, I can shed some knowledge to others who want to exit consulting and go into tech — by decoding all this Bay Area jargon.

I get asked a ton about the kind of jobs that former consultants typically go into.

The simplest way for me to break it down is into three buckets, organized by the best fit in terms of capabilities:

- Perfect Fit: these jobs are a direct translation of the skills that consultants build; the learning curve will be very gentle in these roles

- Okay Fit: consultants can thrive in these jobs, but candidates are going to need to tailor their story and experiences to be competitive in the hiring process

- Additional Work Needed: many former consultants break into these roles, but consultants will need to go above and beyond in order to get one of these jobs; additional work experience or education may help

I also want to preface that I have obviously not worked in all of these roles, so everything I say will be my own perception of the jobs from my singular experience at my current employer.

If you disagree with my interpretations, let me know by commenting in this article.

The Perfect Fit Roles

Corporate Strategy

The corporate strategy team handles a lot of big, high-level questions for the executive leadership team: what are our business priorities and objectives for the next year, what macro-trends do we want to capitalize on, what new markets should we play in.

A corporate strategy associate is typically assigned to a handful of time-boxed projects at a time — being deployed across any given function or team at the company.

He/she often is given an ambiguous question (e.g., what will this product’s revenue forecast be in the next 2–3 years — given certain scenarios) and works independently to solve it.

Consultants who enjoy “blue sky” strategy cases will fit well in the corporate strategy team. If you’re interested in model building, slide making, and generally just being an internal consultant, this role is a perfect fit.

Many formal consultants who enjoyed consulting but wanted a better work-life balance and wanted to work within one company will opt to work in this role.

Business Operations

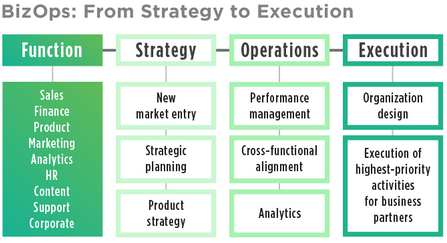

Business Operations (BizOps) can mean a ton of different things depending on the company; broadly speaking, a BizOps associate is a fire fighter — he/she puts out any high priority fire that’s happening in the company.

Sometimes, that means a BizOps associate plays a similar role to Corporate Strategy — tackling tough high-level questions for executives.

Other times, a BizOps associate may be tasked with something more tactical — like fixing a broken process. For example, a company may have terrible sales conversion and not know why, and the Head of Sales will deploy a BizOps team member to get to the bottom of it.

Like Corporate Strategy, BizOps has many time-boxed projects on their plates; and both roles spend a lot of time on Excel and PowerPoint.

However, unlike Corporate Strategy, BizOps needs to wear many more hats — context switching between both high-level and low-level problems. BizOps is also more execution-oriented, meaning their tasked with owning the problem and solution end-to-end.

This typically means a BizOps associate is in the weeds with a team to implement a solution and measure its impact.

Chief of Staff

A Chief of Staff (CoS) role is even more variable than a BizOps role; not only is it dependent on the company, it’s also dependent on the leader that you report to.

A CoS is, in some sense, the “right hand” of a leader/executive at a company; a CoS deals with the day-to-day operations of supporting a leader.

If you’re fresh out of your two-year stint in consulting and at a startup, you may be the sole CoS to your leader. If you’re a bit more senior and at a larger company, you may be the leader of an Office to the CXO — with many associates reporting to you.

It’s impossible to perfectly capture everything that a CoS does in a succinct manner, but at a high-level, a CoS has three responsibilities:

- Operating model: a CoS ensures that everything runs smoothly for a leader’s team — setting the meeting cadence, the staff meeting agenda to give prioritized visibility to the leader, the sub-team objectives to ensure individual incentives are aligned with the team goal, and reporting of said objectives

- Organizational liaison: a CoS is the connective tissue across the leader’s team, as well as between the team and the broader company — synthesizing the most relevant and high-priority information to a leader; helping a leader prepare for conversations with the Board, CEO, or other executives; taking the first pass at internal and external comms for the leader

- Special projects: a leader often delegates confidential and high-priority problems for the CoS to resolve. This looks a lot like a BizOps role, where a CoS may be tasked with changing the team’s organizational structure, reimagine the recruiting process, or look at macro-trends affecting the team.

CoS is a pretty unique position that gives you exposure to high-level executives at a company. At times, a CoS may even be called on to make decisions on behalf of a leader (e.g., green light a deal, decide on trade-offs for a strategy).

On the flip side, a CoS role can be administrative at times: building memos, rearranging meeting agendas, updating progress report slides.

In addition, CoS is a temporary gig — with many former consultants serving the role for a few years before landing on a role with a more clear promotion path.

Product Marketing

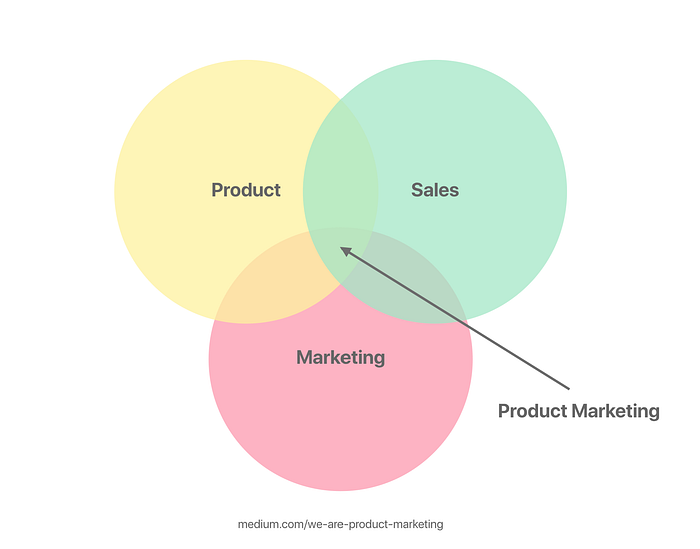

Sometimes called “go-to-market strategy” or “GTM strategy”, Product Marketing is essentially the business side of launching products — a complement to the product and engineering teams.

Product Marketing (PMM) takes an idea from 0 to 1, and then from 1 to 100.

From 0 to 1, PMM works with product and engineering on shipping a new product. PMM typically conducts research on the new market, new customer segments, and existing competitors and their business models.

While prototyping a new product, PMM may start to identify and refine the target customer segment, as well as think through customer acquisition and monetization strategies. With the target customer segment, PMM thinks through the hypotheses for messaging and value proposition for that specific segment and works with Product to validate them.

Post-public launch of a new product, PMM brings the product from 1 to 100. He/she refines pricing, refines the messaging, and works to enable Sales with collateral—like demo videos, pitch decks, and one-pagers — to better close a sale.

PMM is a great fit for consultant who have done pricing optimization cases, or cases where a client is launching a new product.

Program Management

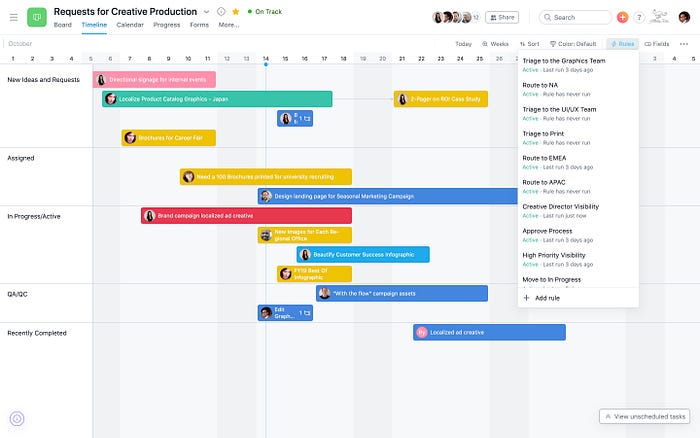

A Program Manager is the air traffic controller of a company. He/she organizes and coordinates all the disparate workstreams of a project — in order to ensure its timely and successful completion.

Program Managers have a strong sense of ownership, serving as the project’s point-of-contact for the rest of the organization. They’re typically on high priority, high visibility projects and have a lot of responsibility in ensuring a successful implementation.

They work a lot in project management tools like Jira, Asana, and Excel, and they are well versed in hosting stand-ups for progress updates.

If you’ve done Program Management Office (PMO) work in consulting and enjoyed the ability to orchestrate a project from start to finish, then this role is a good fit for you.

Like consulting, program managers need to be incredibly structured — organizing all the work of a project into a digestible format. They also need to be clear communicators and command the respect of every team member, in order to ensure accountability.

Keep in mind that many tech companies have Technical Program Managers (TPM) who manage the sprints and releases for engineering teams. If you don’t have a software engineer background, it’s best that you stay away from applying to those roles.

The Okay Fit Roles

Strategic Finance / FP&A

I’m probably triggering a couple people by putting these two roles together, so apologies if I’m being too loose with my bucketing.

Strategic Finance (StratFin) is similar to Corporate Strategy in the sense that the team handles important, high visibility projects for a company’s leaders. However, they tend to solve those projects with financial analysis.

For example, a StratFin associate may build a model that projects the path to monetization of a company based on various scenarios.

I personally don’t work with anyone in StratFin at my company, so this is just what I gleaned from conversations with friends.

Financial planning & analysis (FP&A) is thematically similar — although a far more structured and detail-oriented activity.

FP&A analysts forecast the cost base of a company on a quarterly basis, projecting the cash burn rate of a startup and giving executives visibility into the company’s costs.

Consultants that enjoy model building and have strong analytical skills will be a decent fit for this role. I put these roles in the Okay Fit bucket, because investment bankers tend to be more qualified for these roles.

However, if you’ve been on a ton of due diligence (DD) cases or just cases with heavy modeling required, you’ll do fine in the interview process.

Corporate Development

Corporate Development (CorpDev) is the M&A function of a company. They acquire companies.

Unlike a Private Equity firm, CorpDev doesn’t acquire companies purely for ROI. At a larger tech company, CorpDev may have an investment mandate of increasing shareholder value — such as acquiring a company to gain share in a market, or merge with a company for cost synergies.

At a startup, CorpDev may have a slightly different mandate of improving the product— acting similarly to a Business Development team — or hiring great talent through acquisition.

Like StratFin, CorpDev is heavy on model building and investment deck creation. Investment bankers may be better suited for these role, but consultants with relevant DD experience are competitive as well.

Business Development / Strategic Partnerships

Business Development (BD), also sometimes referred to as Strategic Partnerships, is a business function that expands product adoption through deals and partnerships.

The BD team establishes collaborations with organizations, such as large industry players, universities, or the government, in order to further a company’s business objectives.

They close big, bespoke deals that can step-functionally improve their company — whether it be a lighthouse customer to drastically increase sales or an infrastructure partner to improve the product.

BD is a pretty great career path and generally takes in associates from a variety of backgrounds.

Like consulting, BD associates need to have great communication and interpersonal skills. Just how a consultant has a good read on a client’s emotions and desires (we used to call it seeing underneath the iceberg), a BD associate needs to be able to do the same with a prospective player and play off their emotional state.

However, unlike consulting, BD has a strong relationship management and pipeline component to it — more like a sales role. BD associates need to keep warm leads for months, they need to know what levers to pull on constructing a deal, and they need to know how to close.

If you’re coming from consulting, you’ll need to highlight your experiences that really showcase those capabilities.

Growth / Digital Marketing / Marketing Analytics

Again, I’m probably triggering people by putting these two roles together (again, it totally varies by company), but IMO they require a pretty similar skill set.

Each of these three roles has a customer acquisition component, an analytics component, and an optimization component.

Customer acquisition. These roles want more people to look at and beware of their company. They may do things like run a Youtube ad campaign or pay for some keywords on Google search so that the company website pops up under the sponsored results.

These roles also ultimately want people to do some action that benefits the company. Either buying a product or downloading an app or connecting the company with another company’s vendor management team.

In order to link the Youtube campaign to an actual app download, there needs to be data instrumentation in place so that these roles can analyze the effectiveness of the campaign.

Is $10 per app download good? These roles should know the answer.

Finally, these roles want to optimize the spend of these campaigns. Or they want to optimize the likelihood that a person seeing the campaign will download an app.

Optimize, meaning run experiments. Change the length of an ad, switch the location of an ad, play around with the color and design of the homepage.

Maybe these roles see that people really like the ad on Youtube but not on TikTok. Or maybe these roles see that more people leave if the homepage doesn’t have a fun graphic as the hero.

They’ll optimize accordingly.

In some companies, Growth is under the Marketing team; in others, Growth is a standalone team or a part of the Product team. In the latter scenario, Growth has a larger mandate and full product ownership on how to said mandate.

For example, a Growth Associate — sometimes called Growth Hacker — is tasked with increasing user activation for a B2B SaaS productivity product; companies are buying software subscriptions but their employees aren’t logging on and using it. Come time for renewal, the company will see low usage of the SaaS product and choose to not renew — i.e., the cohort attrition rate will be high, and therefore costly for the B2B SaaS company.

This is a larger scope than a Growth Marketing Associate, who is mainly interested in increasing conversion for top-of-funnel activities like website visitors or newsletter signups.

This Growth PM may have a team of Growth Engineers who build and ship features to increase user activation — features like reminder emails and single sign-on integration. This Growth PM may have a really good sense of why users aren’t activating their accounts, and may spec out features that remediate the funnel drop-off.

If you’ve been on a marketing case, or if you’re great with analytics and optimization, you can apply to these roles. However, this is a rather niche skill set, and there will likely be other candidates who have down this work before at other companies.

Product Operations

I’ll be honest — I’m not entirely familiar with a Product Ops role; I‘ve typically seen them in larger companies (like Series D+). But the ethos behind this role is to improve the effectiveness of the Product team.

A Product Ops associate works closely with the Product team, supporting the team by being the source-of-truth for specific Product activities.

Before spec’ing out a feature, the Product team may turn to a Product Ops associate to be the source of truth for all user information — driving user research and interviews and distilling themes into documents for the Product team to digest.

After a feature is shipped, a Product Ops associate helps the Product team conduct experiments and analyze the experiment data to help Product make better-informed decisions. Or, the Product Ops associate may document the feature in a digestible way and train the customer-facing teams on how to talk about, sell, or troubleshoot the new feature.

Since it’s a rather niche role, companies would prefer to hire a candidate with previous Product Ops or product-related experience, but consultants can be strong candidates for the same reason why they’re competitive for Business Operations roles.

Consultants may see this role as a great gateway to becoming a Product Manager for two reasons: (1) it’s a role that has more capability overlap with consulting than Product does; (2) it works closely with the Product team so you can slowly ramp up to being a Product Manager.

Product Analytics

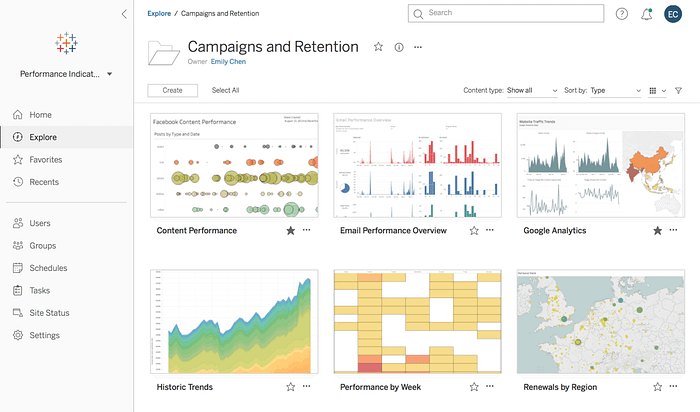

The Product Analytics team is a great fit for consultants who really love working with data and producing insights from data analysis.

Product Analysts measure product adoption and usage and build reports to give visibility to internal stakeholders like Product Managers, Business Operations, and executives.

They may also work with the product engineering team to set up the right data instrumentation to measure and track product usage.

In an ideal world (i.e., as portrayed in the Lean Startup), Product Analysts are embedded into the engineering sprint team so that the team sees the impact of the features that they ship.

To be a great product analyst, you’ll need to know a querying language (like SQL) and sometime a language for statistical regressions (like R or Python).

You’ll also need to be familiar with data visualization tools (like Looker or Tableau) in order to create helpful dashboard and reports for your analyses.

The Additional Work Needed Roles

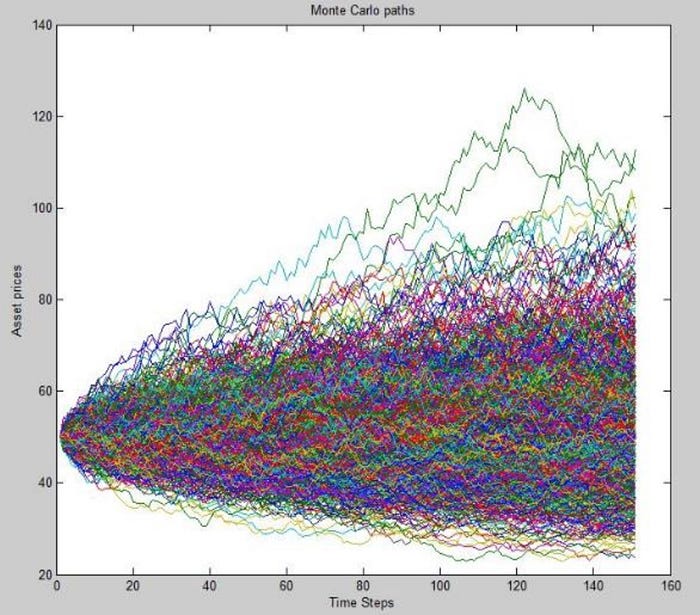

Data Science

Data Scientists, in an oversimplified sense, are a level up of Product Analysts.

They can analyze product usage data, and they also have a strong skill set in statistical modeling and computational algorithm building.

Depending on the product, a Data Scientist can be a part of the engineering team in shipping new features. For example, data scientists can help build rider-driver matching algorithms for a rideshare app.

In other organizations, a Data Scientist supports experiments for the product team. For example, a Product Manager may experiment with a variety of small features to increase engagement; a Data Scientist would analyze the data to truly discern the impact of the new features.

Sometimes, a Data Scientist has research-based projects — where they build predictive models to forecast scenarios. Here, they may build machine learning algorithm or other advance analytics tools.

Candidly, it’s pretty hard for a consultant to become a data scientist — unless they have a Computer Science / Statistics background and have experience in advanced statistical regressions.

If you don’t have that experience, I recommend enrolling in a data science bootcamp or going back to school to formally learn data science.

Product Management

Commonly mistaken for a Program Manager, a Product Manager (PM) is a very different role in tech.

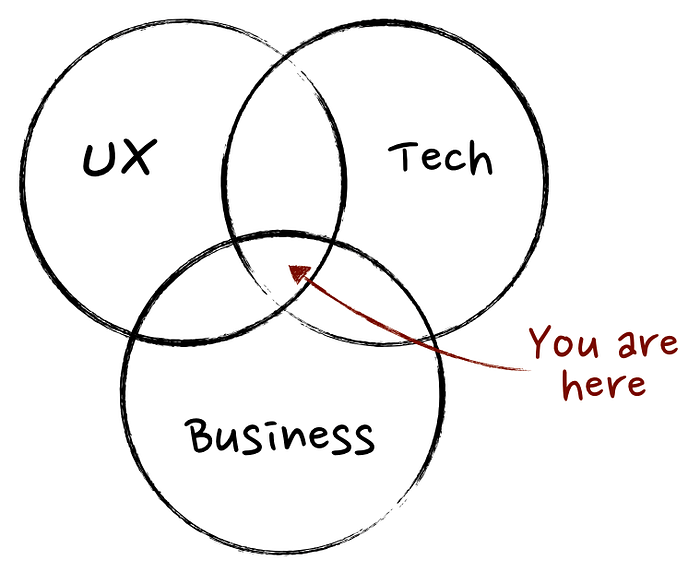

I could go on and on about what a PM does, but to put it succinctly, the PM sits in the intersection of business, design, and engineering. He/she champions the voice of the customer and ensures that the product delivers maximum impact for the customer experience, as well as achieves business goals.

Consultants have the potential to become great PMs because they have great cross-functional collaboration skills — they need to work well with the sales/BD teams, the engineering teams, and design teams.

They also have great information synthesis skills; it’s a lot of wrote to take in all the requirements for a feature and distill them into a concise Product Requirements Doc (PRD).

In addition, consultants are great at data-driven decision making, which PMs need to do in order to prioritize features and build roadmaps to drive toward user and business outcomes.

Unfortunately, PMs are also well-versed in engineering. They understand systems design and technical trade-offs for a feature. Depending on the company size, they may also lead engineering sprints and write technical design docs, so being able to communicate on technical details with engineers is incredibly important.

Moreover, PMs work a lot with designers, so they need to understand concepts like wireframes, user journey maps, and personas really well.

Luckily, consultants are quick learners and can get up to speed on technical details in little time; however, most company want their PMs to have a technical background off-the-bat.

I’ll probably do a follow-up post on how to break into Product — since it’s a pretty common question that I get asked.

IMO the best course of action is one of two strategies: (1) have a side project that showcases your product abilities; (2) join a position that works closely with Product — like Product Ops, BizOps, or Chief of Staff — and transition internally into a PM role.

People & Communications

I’m lumping these two teams together because they have similar hiring themes — even though they’re actually really different in terms of day-to-day work.

For People, you’re in charge on recruiting, learning and development, and HR. For Comms, you can be in charge of internal comms or public relations for the external face of the company.

I believe that former consultants can really thrive in this role — as there is a lot of problem solving and clear communication required. In addition, consultants can always do an analytics-centric role in a People & Communications perspective.

However, from my experience, companies favor candidates with previous People/HR or Communications experience.

Product Designer

A Product Designer — sometimes called UX Designer — is responsible for creating the user experience (UX) and, depending on the organization, visual design of a product.

Along with the PM, the Designer champions the voice of the customer, deeply understanding the customer journey and the pain points / moments of truth along the journey.

If you have a Design degree or you’ve been on a few design-centric cases (e.g., reimagining a customer journey using design thinking), then you may have a shot at working as a Product Designer.

Otherwise, you’ll likely not have a chance in the hiring process — compared to formally trained Designers. It’s likely best to get a degree or enroll in a bootcamp.

Everything Else

I tried to be exhaustive with my list, but I’m sure that I missed many job roles — especially jobs at a Facebook/Google-type where titles become more obscure (e.g., Revenue Ops, Product Specialist, Business Lead… sometimes you just need to read the JD).

I also believe that a former consultant can get any job he/she wants with the right amount of effort and education.

If you want to be a lawyer in the company’s Legal team, then you’ll need to go to law school. If you want to work in sales or account management, you’ll likely need to work an entry-level sales job and work your way up.

If you want to become a software engineer, you’ll either need to dust off your Computer Science degree, or if you didn’t study CS, you’ll need to join a coding bootcamp or self learn.

The world is your oyster!

It’s also worth noting that this list only ranks positions by capability fit. There are plenty of other factors to consider when choosing a role — comp, upward mobility, learning and development, interest in function.

Please don’t hesitate to reach out here or on LinkedIn if you have any questions!

Additional Resources

My friend Juliette runs an awesome search firm Opus that helps consultants and bankers join startups.

Ali Rohde has a great Substack called But What Do You Actually Do that offers deep dives on each tech role and what it really means to do them.